- Home

- Pet Owners

- Advice for Reptile Lovers

- Reptile Health & Welfare

Reptile Health & Welfare

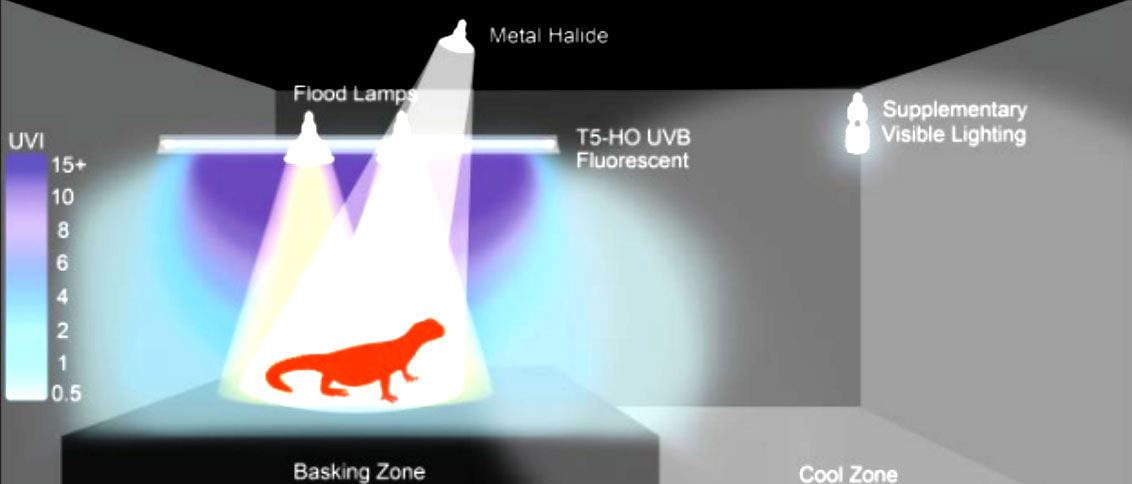

Proper husbandry is crucial for maximizing the health and welfare of captive reptiles. It is essential to know why each component of a reptile’s housing is needed (e.g. UV lights), and to know the species-specific requirements which differ between the diverse range of species (e.g. humidity levels). Reptiles are becoming increasingly popular as pets. The following information provides tips on the basic care of reptiles. NUTRITIONNutritional requirements of reptiles are highly varied. All snakes & crocodilians are carnivorous, some lizards like iguanas are herbivorous, while others are omnivorous, like bearded dragons. Others will change their diets as they grow, such is the case with many species of chelonians (turtles, tortoises, terrapins). Before getting a reptile, it is essential to do your research to determine what should be included in their diet. Commercial insects and rodents are available at many pet shops as a major source of protein and fat. Those diets that require plant, vegetable or fruit matter should be sourced fresh. Snakes require whole prey animals as their diet; the frequency and size of the rodent will be dependent on the snake’s size and age. Those reptiles that do not eat whole prey, will require calcium supplement (purchasable at commercial pet shops) to be mixed with their feed. This (along with correct UV provision; discussed later) will prevent them from developing Metabolic Bone Disease (MBD), which is a common condition plaguing captive reptiles. Note: Try to feed your snake in a separate tub to their enclosure. If fed in their enclosure, they will be conditioned to expect food when you approach, and this can result in a nasty bite! Feeding in another tub will prevent this goal-directed aggression. WATERThe way we provide water to our reptiles is species dependent. Some will only lap moisture off vegetation, and therefore will require daily misting in their enclosure. Others will accept water from a bowl. If herbivorous or omnivorous, these reptiles will get some water from their green vegetables. But this should not be their only source of water. If these animals are not accepting either of these methods, they may drink when bathed or when water is dropped onto their snout. ENCLOSURE & HEATEnclosure requirements will differ depending on whether your reptile originates from tropical, temperate and arid climates, among others. Once again, species-specific natural history needs to be researched for this. The important thing to know is that the size of the enclosure (and the age/size of the reptile) will determine heat exposure. Formulae have been established to calculate the appropriate enclosure size requirements according to the size of an animal, for example in the following paper: ‘Guidelines for inspection of companion and commercial animal establishments’, written by Warwick, C.; Jessop, M.; Arena, P.; Pilny, A.; & Steedman, C. This leads into another central component of keeping reptiles: TEMPERATURE. Reptiles differ from mammals via their method of obtaining heat; they can only regulate their internal temperature to the temperature of their surroundings. Hence, enclosures should also be fitted with an infrared spot heat lamp or another heat supplement. The wattage of this lamp is dependent on the size of the animals, time of the year and its PBTZ (preferred body temperature zone). A thermostat should be connected to the lamp for temperature control. A temperature gradient throughout the enclosure is more important than the absolute temperature requirement. That is, there should be a hot end of the enclosure, where the reptile can reach its PBT (for an example, see Figure 1). PBT have been widely researched and determined for many species. This will be a basking area directly under the heat lamp (but so the reptile is not at risk of touching the lamp). Self-heating rocks are inadvisable as they can cause burns, but normal rocks or logs are good basking objects. There should also be a cool area in the enclosure where the reptile can escape the heat if needed. For more information on enclosure set up and PBTZ for individual species, see textbook ‘Reptile medicine and surgery in clinical practice’ (by Doneley, B.; Monks, D.; Johnson, R.; Carmel, B).

(ABOVE IMAGE) Figure 1: Example of enclosure with a basking end, and a cool end. Also note the different types of lighting. Image from Doneley, B.; Monks, D.; Johnson, R.; Carmel, B. Reptile medicine and surgery in clinical practice. John Wiley & Sons: 2017.4. SUBSTRATEMany substrates can be used for the bottom of the enclosure, with pros and cons for each (these can be found in textbooks or online). It is suggested by many to prevent loose substrate as it can lead to intestinal impaction if ingested. This may be side-stepped by feeding your reptile in a separate tub to its enclosure. It is good practice to spot clean tanks regularly, by removing faeces and other debris. And then disinfection with veterinary-grade disinfectant (like F10, also available at pet shops) regularly, but less frequently. UV LIGHT

Captive reptiles (except snakes) require UVB light to absorb nutrients and stay healthy (specifically to prevent MBD development, as UV is closely associated with the production and use of Vitamin D in the body). There are several different types of UV lights, and requirements will change (unsurprisingly) between species, e.g. nocturnal species will require different lights. Generally diurnal species will require 10-12 hours of UV light during the day, which is then switched off at night; to mimic normal day length. Often pet shop staff will be able to help you with the decision, but also do your research! SOCIAL LIFEMany species of reptile are solitary. However, some species have complex social structures that we are only just beginning to understand. Generally, it is recommended to keep reptiles in separate enclosures (especially males), with some exceptions including breeding pairs and small groups of similarly sized females (species dependent!). With thanks to Amelia Benn, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine Student (expected completion date 2020) University of Adelaide, for sharing this information.

|